On Buying a Cow, a Hog, and Knowing Your Food

TL;DR – Is buying meat in bulk worth it?

We bought 1/2 a grass‑fed, grass‑finished cow and 1/2 a pasture‑raised hog from a local Idaho ranch.

This was not primarily a cost‑saving move — it was about quality, ethics, food security, and supporting our local community.

Total cost: ~$3,500 all‑in for beef + pork, including processing.

We ended up with a freezer full of high‑quality, customizable cuts that will last us a long time and reduce regular grocery costs.

Buying in bulk requires freezer space, flexibility, and trust in your rancher and butcher, but offers transparency, resilience, and connection to your food.

If you care about where your food comes from and have the means to store it, buying meat in bulk can be incredibly rewarding — just don’t go into it expecting miracle savings.

One of my favorite things about living in Idaho is how rich the agriculture industry is here — there are so many producers of meat, dairy, vegetables, fruits, honey, and more that you can successfully meet most of your food needs through local family businesses, if that’s important to you. Since food is one of my favorite things in life, I’ve always been aware of the benefits of locally grown and raised goods, but I haven’t always been surrounded by — or fully aware of — the variety of options I seem to have now. For the past two years of living here, I’ve made it a priority to buy as much as I can from local farms and ranches — not only because of the significant increase in quality, but to support our local economy and invest in our neighbors.

I was involved with a project a couple of years ago that required me to learn a lot about the meat industry — specifically beef — and through that experience, I became increasingly set on the idea of acquiring a bulk share of an animal. As the national food industry continues to get weirder and weirder, and people lose trust in supply chains and food quality despite ever‑increasing costs, it started to feel more logical to secure a sustainable, high‑quality food resource we could rely on.

The idea of having that much meat initially felt daunting, but when I stepped back and considered the flexibility it would give us in how we cook and eat, it quickly became exciting.

In full transparency, most of the knowledge I have about meat — and the opinions that led me to this decision — center around beef. My knowledge of pork is much more limited, and buying a hog was mostly a “well, fuck it — if we’re buying a cow, we might as well buy a hog too.” We primarily eat beef in our house, but occasionally spring for a nice pork chop. Honestly though, there are times I prefer a fatty pork chop over a steak.

To make one thing really clear: this was not a cost‑saving effort. It would be great if the end result turned out cheaper, but since there’s no way to know exactly what your beef share will cost until it’s harvested, you can’t depend on that. More on that later. If you’re only interested in what we paid, feel free to skip ahead.

Our rack of beef when we picked up our ½ beef share

Choosing A Ranch

I would love for a substantial portion of my diet to come from wild game. Unfortunately, I haven’t quite reached the “becoming a hunter” stage of life yet — though it’s pretty high on my to‑do list. Aside from hunting, purchasing a locally raised animal is about the most ethical way to source meat protein. These animals are (usually) deeply cared for by people whose livelihoods depend entirely on producing a quality product. Their health, happiness, and overall well‑being are top priorities — and there really is truth to the idea that happy, healthy animals yield better food.

When it came time to pick a local ranch for beef and pork, I had a lot of options to sift through. According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, there were 7,259 livestock producers in Idaho, while the Idaho Beef Council cites over 7,300 ranchers statewide. Either way you slice it, that’s a lot of choices. I spent about a week digging through websites, blogs, Reddit, Facebook groups, and reviews before ultimately landing on McIntyre Family Farms based on what mattered most to me.

We’ve ended up being really happy with our choice and everybody I worked with/spoke to at McIntyre, Greenleaf Meat Packing, and Northwest Premium Meats were all so lovely and incredibly helpful. I have nothing but positive things to say about our experience overall and would work with all of them again without thinking twice.

My Priorities

Grass-fed and grass-finished beef and pasture-raised pork

Animals that were raised within ~2 hours of Boise

A business that allowed you to work with the butcher to customize your cut-sheet and packaging preferences — this was probably my number 1 priority.

Sometimes when you buy an animal, you receive a standard list of cuts. That’s great for many people, but I wanted more control based on how we actually cook and eat. Since Chris is gone a lot of the time, I wanted steaks wrapped individually and roasts in smaller portions. I also wanted non‑traditional cuts like tongue, cheek, and tail.

A business with sustainable practices

Hormone/antibiotic free meat

Regenerative agriculture practices, or, at minimum an emphasis on land and ecosystem health

Organic practices, even if not organic certified (which is largely just a huge marketing scheme, rant saved for later)

A true “half an animal” share - fifty percent of all cuts available — split down the middle hot‑dog style, not hamburger style (forgive the analogy).

Some additional insight/knowledge into these things and why they were important to me:

Grass-fed and grass-finished vs. grass-fed and grain-finished. Most beef found in grocery stores — unless otherwise specified — is grain-finished. To be fair, neither one of these are “better” scientifically, they’re just different. If you want to read some science (actual peer-reviewed science) about it, you can here.

There is a nutritional difference and a flavor difference when it comes to how your beef is finished. “Finishing” is the process a beef goes through at the end of its life right before it is slaughtered. Grass-fed and finished beef is raised entirely on grass, while grain-finished beef is primarily raised on grass before being moved to a feedlot to be finished on a grain-based diet for a period before slaughter in order to fatten the animal up faster.

Nutrition: Grass-finished is often leaner and richer in omega-3s and vitamins, while grain-finished beef is typically fattier.

Taste: Grain-finished beef is often preferred by those who like a classic, rich, and buttery beef flavor. Grass-finished beef has a more distinct, sometimes grassy flavor that some people enjoy — It’s almost a gamey beef.

Cost: Grain-finished beef is often less expensive because grains are more affordable and the finishing period is shorter, allowing cattle to reach market weight faster.

Sustainable farming practices - while McIntyre doesn’t claim to use regenerative farming, they do have a long list of ways that sustainability is at the front of their business. (The following is directly from McIntyre’s website.)

Pasture based

Grass-Fed Beef - Cows are grazed on grass and intensively managed; depending on the time of year they are moved daily or sometimes multiple times a day. When the pastures are snow covered or frozen down, cattle are only fed grasses, hays, and baled cover crop. No grain ever.

Pasture-raised pork - Hogs are rotated on their pasture and are free of crates. Their supplemental feed is non-GMO and corn free. We grow and harvest their ration right here on the farm; peas, triticale, lentils, barley, and then add charcoal and minerals.

Responsible farming

No-till farming - We try to disturb the soil as little as possible. We believe that what is happening below the ground is just as important as what is happening above. We try to do everything that we can to feed our soil. This is accomplished using no-till practices.

Low carbon footprint - Animals are fed from plants grown on the farm. Many producers have to buy feed from other farmers, using extra fossil fuel to haul the feed to and from farm. All Feed is ground/made on our farm.

Hormone/antibiotic free - We don't believe in low doses of antibiotics to help animals gain weight faster.

Humanely raised, harvested, and traceable - We breed for docile animals, this leads to less stress for animals and humans. Animals are raised in small batches, free from confinement and Each animal is harvested one at a time, the old fashioned way at local establishments, and inspected by the USDA. Unlike large kill facilities, each package of meat we sell, can be traced back to a single animal

The Process

When buying a beef share, you typically have the option of purchasing a 1/4, 1/2, or whole animal. Price per pound generally decreases as the share size increases. Costs vary widely depending on location, breed, feed, animal welfare practices, and the ranch itself. Pork works similarly, though hogs are smaller, so most farms offer only half or whole hogs.

Another variable is timing. Sometimes you’re buying meat that’s already been processed and frozen; other times you’re reserving an animal for future harvest. That depends on the size of the operation, local demand, and how the farm runs its business.

Freezer space is a real consideration. The amount you’ll need depends on your share size, animal breed, and whether you choose bone-in or boneless cuts. Most farms can give you a general estimate. We own an 11 cu. ft. chest freezer, and the beef and pork filled it completely — with about 15 pounds of ground pork and all the bacon spilling into our kitchen freezer. I was a little too confident in our available space.

Associated Costs

Buying an animal share can be a bit of an uncertainty when it comes to cost if you’re reserving an animal for future processing. When you start looking at pricing, what you’ll notice is that the price will usually be listed as “$ per pound - hanging weight”, which means you won’t really know what it’s going to cost you until you get to butchering time. Hanging weight is the weight of a slaughtered animal's carcass after the head, hide, blood, and internal organs have been removed, but before the final processing into cuts.

Payment structures vary by farm. Sometimes you pay a deposit, sometimes a lump sum, sometimes the farm and processor are paid separately. It all depends on how the operation is structured.

At McIntyre, we paid for the animal based on hanging weight, then paid processing fees separately to Greenleaf Meat Packing (beef) and Northwest Premium Meats (hog). We paid a $150 deposit per animal at reservation, the remaining balance after slaughter, and processing fees at pickup.

To the Farm/Ranch

At McIntyre, their bulk beef prices at the time we purchased were as follows:

1/4 Beef - $6.80/pound, average of 185 lbs.

1/2 beef - $6.55/pound, average of 350 lbs.

Whole beef - not available

And their bulk pork was:

1/2 hog - $3.50/pound, average of 85 lbs.

whole hog - $3.25/pound, average of 180 lbs.

To the Butcher/Processor

The cost through Greenleaf Meats is a $65 harvest fee for a 1/2 animal and 90 cents per pound hanging weight for cut and wrap. Additional price per pound is charged for any cured cuts (pepperoni, etc), sausage (breakfast, italian, etc.), special ground (beef patties for burgers), or jerky. There can be other costs associated with processing preferences as well, for us this was an additional $30/quarter for individually wrapped steaks instead of the standard 2 per package.

The cost through Northwest Premium Meats is a $47.50 harvest fee for a 1/2 hog and 90 cents per pound hanging weight for cut and wrap. Additional price for sausage (breakfast, hot italian, mild italian, bratwurst, etc.) is $1.25 per pound, and for cured products (bacon) is $1.05 per pound.

Beef Cost Breakdown

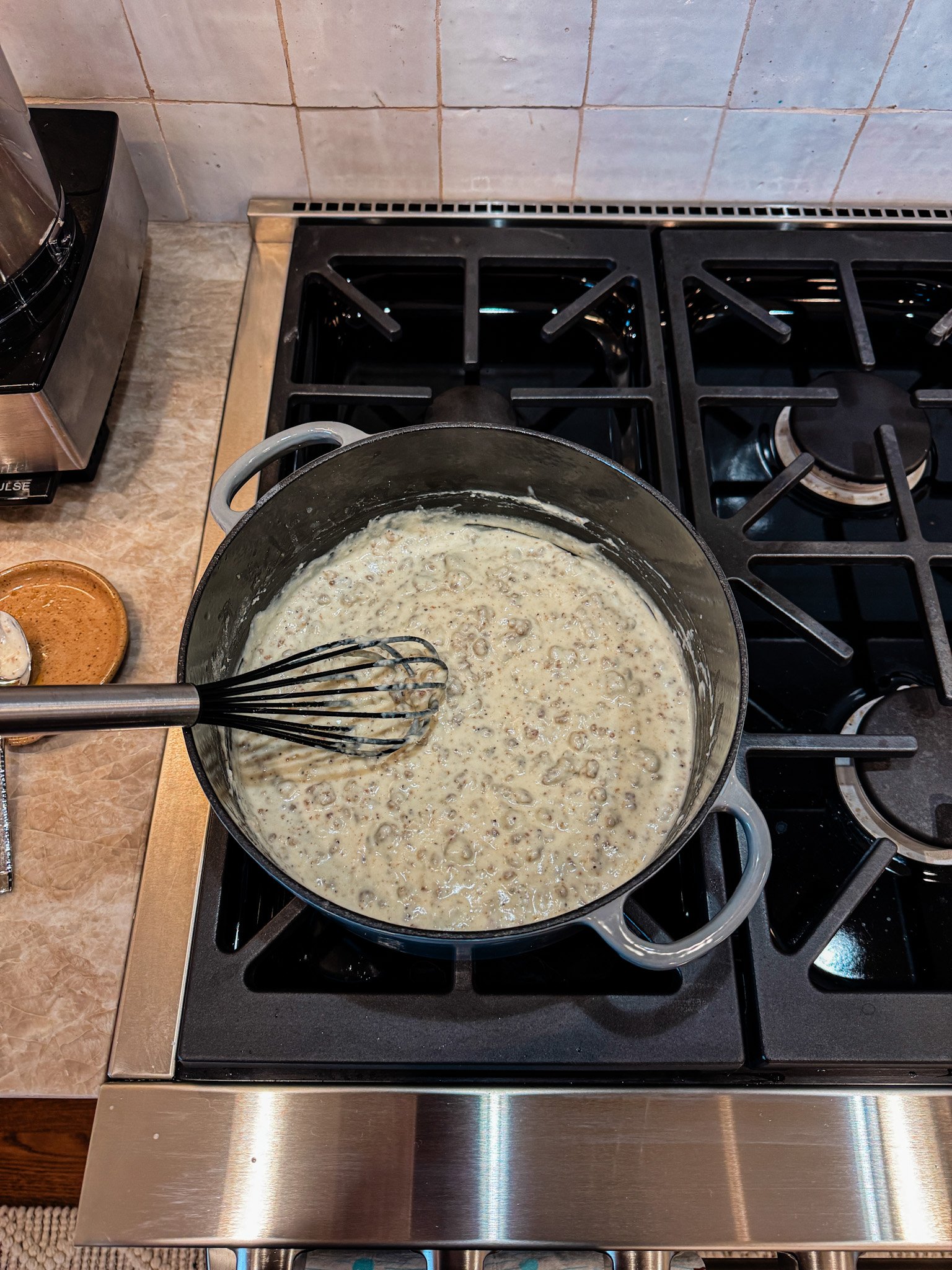

Since I’m a pretty adventurous and seasoned cook, I wanted as many of our cuts as possible to be steaks and roasts. In my personal opinion, you can make goddamn near anything tender enough to eat in steak form when you sous vide it, and that is one of my favorite and probably most regularly used cooking method in our house — especially when Chris is gone.

Our Beef:

Whole beef hanging weight - 757 lbs. | 1/2 beef = 378.5 lbs.

378 lbs. x $6.55/lb = $2,479.18 ($150 deposit paid when we reserved our beef, the remainder due the day after slaughter) paid to McIntyre Family Farms.$65 kill fee + $340.65 ($0.90/lb for cut & wrap) + $30 (fee for individually wrapped steaks) + $80 (jerky and pepperoni processing cost) = $486.53 paid to Greenleaf Meat Packing.

Grand total: $2,965.71

Since Greenleaf doesn’t weigh the total of finished beef and it’s not listed per package (they’re a small operation without the ability to do that) and we didn’t weigh it when we got it home, we estimated that this gave us roughly 200 pounds of beef. That equals about $14.83/lb. of meat spread across ground beef, prime cuts (all steaks were cut to be boneless), brisket, roasts, osso buco, stew meat, etc. We also took the bones for soup bones, and some of the shanks for dog bones. An additional 10 lbs. of meat was used to make beef jerky and pepperoni sticks, so it’s harder to calculate that with the dry-down factor.

Here is what we ended up with once it was packaged. Steaks were cut to a 1-1/4” spec.

67 1-lb. packages of ground beef

15 cross-cut shanks/osso buco

13 New York Strip steaks

11 (fucking huge) ribeyes

4 filet mignons

5 serloin steaks

11 chuck steaks

1 flank steak

6 packages of short ribs

1 package of back ribs

1 rump roast

1 heel roast

2 rib roasts

1 oxtail

1 picanha (needs to be cut into steaks)

10 tenderized round steaks

tri-tip packaged in 2 sections

1 brisket packaged in 2 halves

12 sirloin tip steaks

6 packages of cubed stew beef

Several huge bags of soup bones

1 bag of marrow bones for Ru

Hog Cost Breakdown

Honestly, aside from bacon and porkchops, we don’t eat pork often. As an adult, I have literally never cooked a ham, and really am not a huge fan of ham in general, But we do love sausage… So, in favor of having ground breakfast sausage and hot italian sausage, we eliminated the hams and such and asked for mostly ground aside from the chops. When you only do a half of a hog, you can’t do more than two varieties of ground meat because there just isn’t enough product. So, the cuts we asked for were:

1-1/4” thick bone-in pork chops

Bacon

Spare ribs

Ground pork to be turned into breakfast sausage, and italian sausage

Our hog:

Whole hog hanging weight - 197 lbs. | 1/2 hog = 98.5 lbs.

98.5 lbs. x $3.50/lb = $344.75 ($150 deposit paid when we reserved our beef, the remainder due the day after slaughter) paid to McIntyre Family Farms.$47.50 kill fee + $88.65 ($0.90/lb for cut & wrap) + $35.10 (fee for two types of ground sausage blends) + $8.72 (bacon curing cost) = $179.97 paid to Northwest Premium Meats.

Grand total: $524.72

Here is what we ended up with once it was packaged. Steaks were cut to a 1-1/4” spec, but we didn’t have the option to have them individually wrapped there (or… if we did, I forgot to ask), so they came in packages of 2 steaks per package.

19 1-lb. packages of breakfast sausage

20 1-lb. packages of hot Italian sausage

8.3 pounds of cured bacon

4 packages of bone-in pork loin chops

2 packages of sirloin chops

5 packages of rib bone-in chops

1 package of spare ribs

Honestly, when we got the pork, my life was hectic — holidays were coming, work was chaos, and I was barely keeping my shit together — so I couldn’t even begin to estimate weight of the steaks. My only focus was trying to find room for them in the freezer.

Cost Savings

Now here’s where I justify the use of ChatGPT because I simply do not have the time or energy to calculate all of this out. I asked it to breakdown the cost for all of the cuts I received and the estimated associated weights for both grocery-store pricing and the realistic pricing for premium grass-fed grass-finished beef. (Honestly, who knows how accurate this is, but it’s something.)

This would be grain-finished non-premium beef

Did we save money? Maybe a bit ,Probably not a substantial amount. But what this means for us in the future is:

A freezer full of meat that we can rely on in case of an economic downturn, one of us losing our job, supply chain instability, etc.

Not having to go to the grocery store every time we want to prepare a meal

Super premium quality protein

Lower cost regular grocery store trips only having to buy other assorted lower-cost ingredients (my grocery trips since buying these animals have averaged around $50 instead of the previous $100+)

Assorted cuts of meat that will give us a lot of ability to try new things

The ability to feed our friends and family

While we’re here, I also want to give a shout out to Wilson’s Wild Salmon, which is who we get all of our fish from. The Wilsons are a family out of the Wood River Valley who run a fishing operation out of Alaska in the summers. We order salmon and halibut in 10 pound boxes from them and they deliver it down to us in Boise.

A Final Thought on Community

Lately (or… at least before I left social media) there was a lot of dialogue around the farming/ranching industry and the idea of increasing the import of Argentinian beef. If you know me, you know I’m a bleeding heart snowflake libtard, but you also probably know that I don’t see in black and white. There was a lot of commentary online along the lines of “I’d rather support Argentinian farmers/ranchers than our own who largely voted for Trump” and while I don’t think that I keep any company who would so ignorantly say the same thing, I’d like to share my thoughts and encourage you to see things differently if you happen to align with that belief.

First, Argentina has a wildly complicated political climate, similar to our own. Donald Trump and Argentina's President Javier Milei are both far-right wing presidents with shared ideologies. If you don’t want to support Donald Trump and your own neighbors, you shouldn’t be excited about supporting Javier Milei and people whose successes you will never see or share.

Your community is your community, whether you have the same beliefs as them, or not. Whether you like them, or not. When your car is broken down on the side of the road and someone stops to offer you help, are you going to ask them who they voted for? Or are you just going to accept the help? Invest in your community. Your whole community. Share in the success of seeing your neighbors succeed, even if you don’t think they “deserve it.”

Buying food this way isn’t about perfection or purity — it’s about intention. It’s about knowing where your food comes from, investing in the people who produce it, and building a little more resilience into everyday life. A full freezer won’t fix everything, but it does offer steadiness: fewer trips to the store, more shared meals, and a quiet sense of security that comes from being connected — to your food, your neighbors, and the systems that sustain you.